By Li Wannian (李万年)

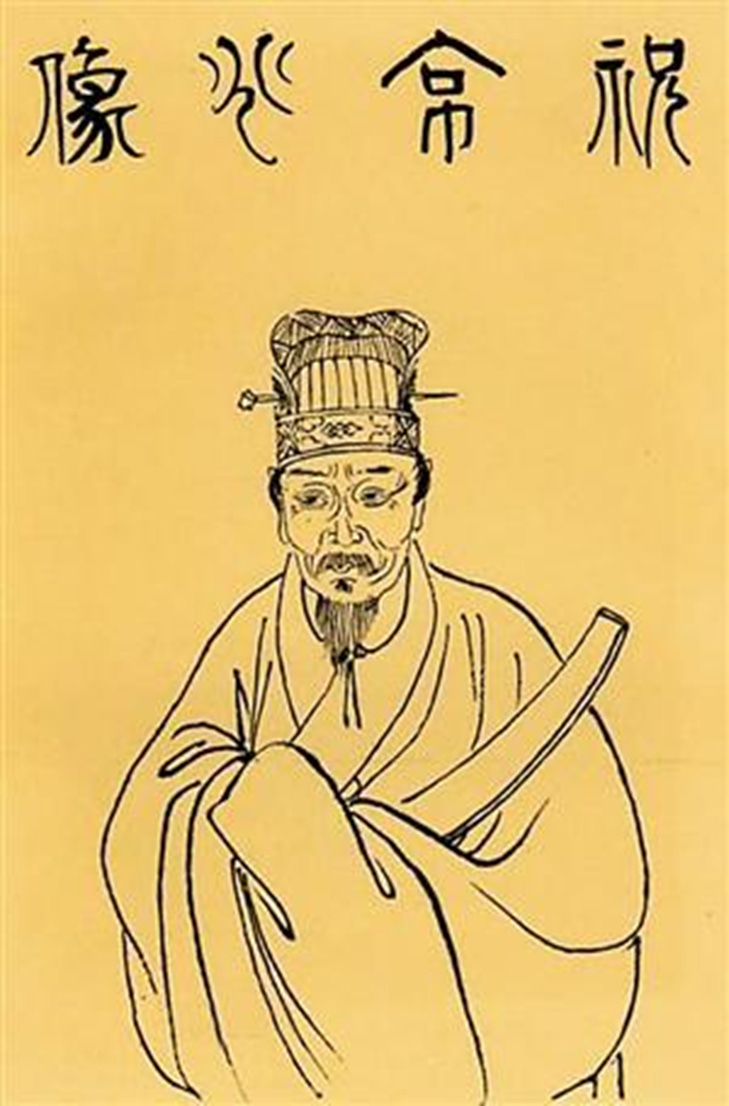

【Editor’s note: Zhu Zhishan (祝枝山, 1460–1526) was a celebrated Ming dynasty calligrapher, renowned for his mastery of regular, running, and cursive scripts. A member of the “Four Talents of Wuzhong,” he synthesized influences from Wang Xizhi (王羲之), Huaisu (怀素), Zhao Mengfu (赵孟頫), and others, developing a distinctive calligraphic style. His works, including Six Scripts Poetry and Essays Roll and Cursive Du Fu Poems Roll, exhibit both precision and spontaneity.

His early regular script was refined and structured, later evolving into a freer form emphasizing fluidity. In cursive script, he infused energy and rhythm, creating bold yet controlled strokes. Deeply influenced by Daoism, he sought artistic transcendence while reflecting his personal frustrations with bureaucracy. His witty personality, seen in both anecdotes and inscriptions, added to his legend. Zhu’s enduring influence on Ming and later calligraphy stems from his ability to balance technical mastery with expressive individuality, securing his place in history.】

Zhu Zhishan (祝枝山, name Yunming, style name Xizhe, 1460–1526) was a remarkable calligrapher of the Ming dynasty. Alongside Tang Yin (唐寅), Wen Zhengming (文徵明), and Xu Zhenqing (徐祯卿), he was celebrated as one of the “Four Talents of Wuzhong.” Together with Wen Zhengming and Wang Chong (王宠), he was also hailed as one of the “Three Great Calligraphers of the Mid-Ming Period.” Born into a family of scholarly gentry and endowed with an extensive intellectual lineage, he showed extraordinary gifts from an early age: at five, he could already write large characters; at nine, he composed poetry; and by ten, he had delved deeply into the Confucian classics and historical texts. Despite repeated setbacks in pursuing officialdom—a life marked by ups and downs—he achieved tremendous acclaim in calligraphy, earning the title of “First in the Ming.” To later generations, Zhu Zhishan’s prominence and influence in the realm of calligraphy remain indisputable. His works, such as Six Scripts Poetry and Essays Roll (《六体书诗赋卷》), Cursive Du Fu Poems Roll (《草书杜甫诗卷》), Ancient Poems Nineteen (《古诗十九首》), Cursive Tang-Dynasty Poems Roll (《草书唐人诗卷》), Cursive Poetry Letters Roll (《草书诗翰卷》), and Taihu Poems Roll (《太湖诗卷》), have been handed down through the centuries and stand as exemplars of Ming-dynasty calligraphic art.

Zhu Zhishan drew from a broad array of influences, adeptly absorbing the essence of earlier masters. His running-cursive script (行草) took its cue, on one hand, from the fluid elegance of the Jin-dynasty calligraphers Wang Xi (王羲之) and Wang Xian (王献之), and on the other, from the uninhibited spirit of Tang-dynasty calligrapher Huaisu (怀素). At the same time, his brushwork bore the measured strength of the Yuan-dynasty master Zhao Mengfu (赵孟頫), with its firm strokes and rigorous structure. In regular script (楷书), he drew upon the Tang-dynasty traditions of Ouyang Xun (欧阳询), Yu Shinan (虞世南), and Chu Suiliang (褚遂良), blending these styles into a unique synthesis. In his later years, he frequently copied the Huangting Jing (《黄庭经》), increasingly emphasizing variations in brush momentum and the interplay of dense and open spaces; through each turn of the brush, his strokes grew ever more powerful and unrestrained, giving his work a progressively radiant quality.

Growing up in the culturally rich atmosphere of Suzhou, Zhu Zhishan was, from a young age, exposed to literary gatherings and poetic exchanges. His own temperament was carefree, and he loved to travel amid mountains and rivers. Combined with Suzhou’s long-established painting and calligraphy heritage, this environment subtly shaped his style. Within Zhu Zhishan’s artistic character lay both boldness and quick wit; coupled with his frustrations in officialdom, the emotions simmering in his heart often spilled onto the page in unfettered strokes. This is especially evident in his “wild-cursive” (狂草) works, where his individualistic flair stands out most vividly.

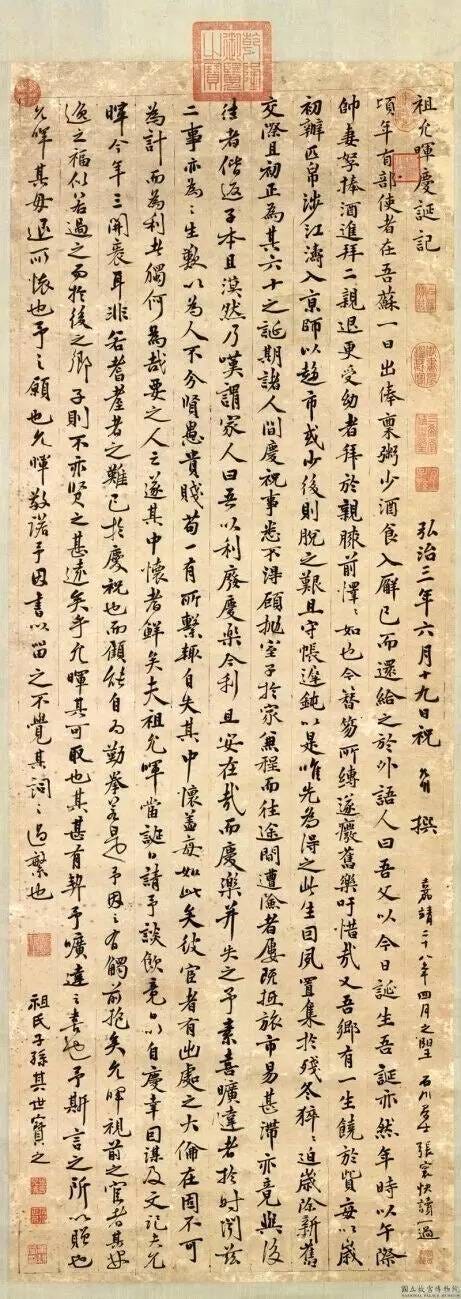

In regular script, Zhu Zhishan was initially influenced by Zhao Mengfu and Chu Suiliang, paying careful attention to precision and discipline. Representative of this phase are Chu Shi Biao's (《出师表》) and related works, whose rounded, compact brushstrokes form upright structures without descending into stiffness, exuding a venerable elegance. Each stroke is crisply lifted and pressed, balancing meticulous form with an underlying dynamism—an indication of his shift from purely emulating the ancients to forging his own path. During this period, he frequently revisited Jin- and Tang-dynasty model books, striving to imbue his methodical brushwork with vitality so that his pieces retained a solid foundation while gradually revealing his personal touch.

In his later years, his approach to regular script took on a freer, more fluid character. Through extensive study of the Huangting Jing, he gradually relaxed the strict shaping of each character, focusing instead on the continuity of brushstrokes and the rhythm of his writing. In certain extant regular-script pieces, one can observe delicate variations in the strokes that infuse the normally upright forms with a sense of movement. He also manipulates spacing with increased ease, achieving a state of “unbound yet orderly.”

“‘Zhi Shan’s cursive is unrivaled under heaven—surely it’s not only in the Three Wu region that fine wine reigns supreme!’” This is how contemporaries praised Zhu Zhishan’s cursive script. Cursive traditions in the Ming dynasty often looked to Huang Tingjian (黄庭坚), Li Yong (李邕), and Mi Fu (米芾) as paragons. Building on these foundations, Zhu Zhishan created something fresh: he preserved a robust, flowing brushstroke while infusing the work with his breezy, uninhibited spirit. His cursive writing exhibits several key characteristics:

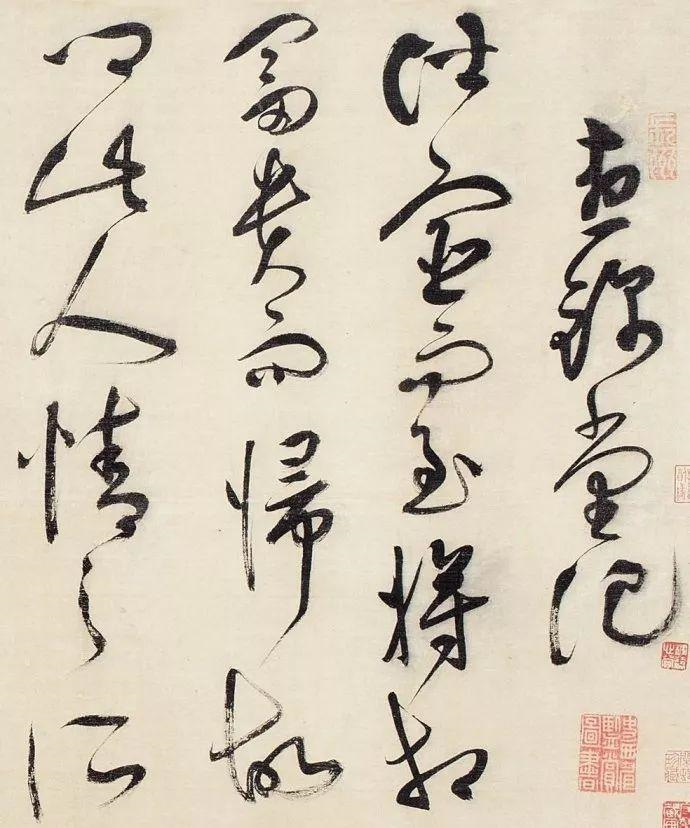

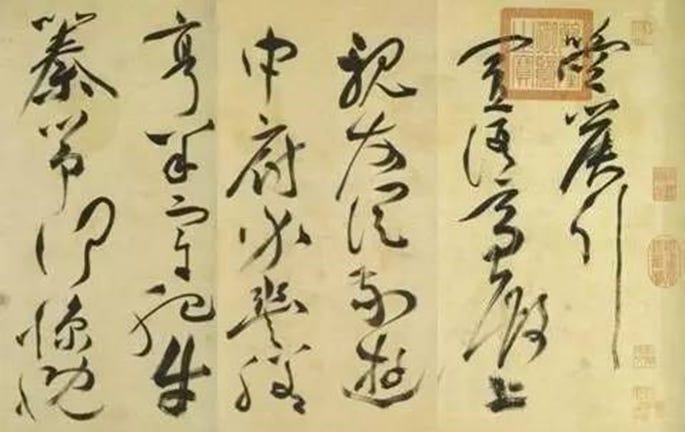

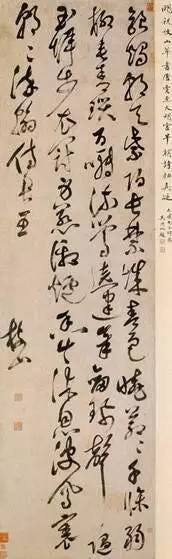

First, his strokes are forceful and supple, each line brimming with elasticity. In works like Cursive Du Fu Poems Roll (《草书杜甫诗卷》) and Cursive Tang-Dynasty Poems Roll (《草书唐人诗卷》), each character’s opening and closing strokes are concise and decisive, its changes of direction and sudden flourishes charged with tension.

Second, his compositions derive momentum from continuous strokes, with an artful interplay of size and pace. Zhu Zhishan’s cursive deftly balances varying rhythms and character dimensions, often linking one glyph to the next in a single breath, yet never descending into chaos. The sweeping nature of wild cursive belies a careful adherence to the logic of calligraphy. In practicing his craft, he meticulously directed the brush’s trajectory and modulated ink flow—whether dry or saturated—to create a cohesive sense of spirited movement.

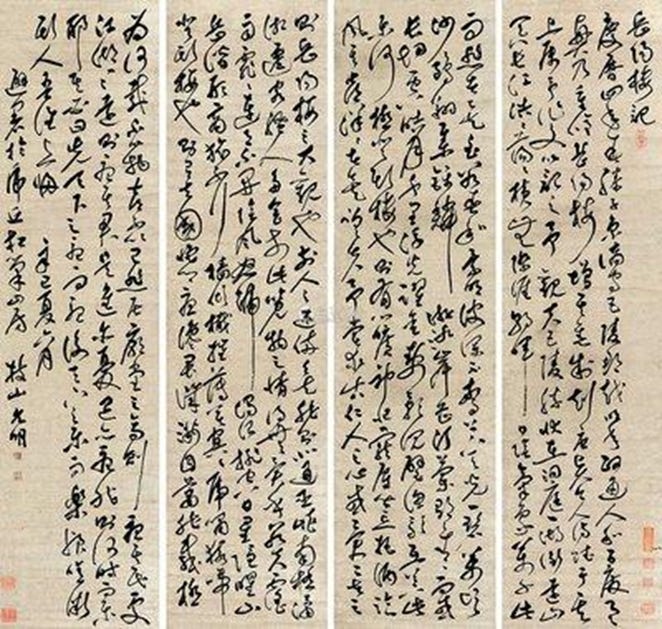

Third, he used cursive to convey personal emotion. In sharp contrast to his frustrations in government service, his writing radiates carefree abandon. Pieces such as Taihu Poems Roll (《太湖诗卷》), Konghou Yin (《箜篌引》), and Chibi Fu (《赤壁赋》) display a fluid grace reminiscent of drifting clouds and flowing water, all while hinting at the artist’s own romantic, unrestrained character. This seemingly “wild on the outside, refined on the inside” ink style distinguishes Zhu Zhishan in the annals of Ming-dynasty cursive, offering an invaluable model for later students of calligraphy.

The artistic value of Zhu Zhishan’s calligraphy lies not only in his extraordinary technical skill but also in the fusion of literati sensibilities and aesthetic ideals. Deeply influenced by the Daoist detachment of Laozi and Zhuangzi, as well as the carefree ethos of the Wei-Jin era, he emphasized spiritual liberation and sought transcendence through the art of the written word.

At the same time, he never abandoned classical orthodoxy. He imbibed the essence of the “Two Wangs” (二王), along with other illustrious predecessors, merging discipline and free expression. In works like Small Regular Script Qian Chu Shi Biao (《小楷前出师表》) and Small Regular Script Hou Chu Shi Biao (《小楷后出师表》), one finds a sense of stately composure offset by lively, intelligent brush movements. Clearly, his pursuit was not unbridled abandon but rather a refined calligraphic realm and an affirmation of the literati’s independent spirit.

That artistic quest is mirrored in his personal life. Far from isolating himself, he forged close bonds with fellow literati like Tang Yin, Wen Zhengming, and others, exchanging creative inspirations. Although he sometimes responded to mundane pettiness with playful satire, beneath the surface lay a dual reflection on both his talent and the state of society. This seemingly flippant style contributed to his later image as both “romantic” and “carefree.”

In terms of quantity, Zhu Zhishan’s surviving works may not rival those of Wang Xi (王羲之) or Zhao Mengfu, yet they retain a considerable place in calligraphic history. His signature pieces—Six Scripts Poetry and Essays Roll, Cursive Du Fu Poems Roll, Ancient Poems Nineteen, Cursive Tang-Dynasty Poems Roll, and Taihu Poems Roll—have enjoyed enduring admiration.

For instance, in the Cursive Du Fu Poems Roll, one sees echoes of Huaisu’s swift dynamism, fused with the elegant linework of Mi Fu, creating a brush style that feels both immediate and transcendent. Conversely, Small Regular Script Qian Chu Shi Biao and Small Regular Script Hou Chu Shi Biao reveal a solid foundation in method and structure from his earlier period. His ability to combine expansive wild cursive with precise small regular script is a hallmark of Zhu Zhishan’s mastery.

His various pseudonyms, “Zhishan Daoren” (枝山道人) or “Zhizhi Sheng” (枝指生), likewise illustrate his multifaceted self-perception. On the one hand, his extra finger on the right hand lent him a distinctive moniker, hinting at a subtly rebellious self-mockery; on the other, the term “daoren”—meaning “Daoist person”—points to his later fascination with Daoism and Zen Buddhism.

Zhu Zhishan was ranked alongside Tang Yin, Wen Zhengming, and Xu Zhenqing, together forming the “Four Talents of Wuzhong.” Yet, compared to Wen Zhengming, his spirit was far more uninhibited, and he shared with Tang Yin a carefree and sometimes roguish attitude. Historical records and popular lore describe the two drifting on boats, wine in hand, composing poems amid scenic landscapes—one anecdote suggests they once spent all their money traveling in Yangzhou, resorting to trading their literary talents for funds. Though likely embellished by theatrical accounts, the story does reveal the pair’s playful nonchalance.

Zhu Zhishan’s wit and dexterity became the stuff of later tales. In one instance, after receiving an insufficient sum for an inscription on Willow Bank Farewell, he initially wrote only “Several willow trees stand east, west, north, and south.” Once he was paid in full, he continued with verses of poignant farewell. This “mischievous brush” episode shows both his stylistic virtuosity and his mocking take on penny-pinching patrons

.

Compared to Wen Zhengming, Zhu Zhishan’s temperament was more extroverted. In his later years, signing himself “Zhishan Daoren,” he embraced the urbane spirit of the Wei-Jin period, retreating into nature and displaying a deeply felt inner freedom. Meanwhile, his reclusive outlook and philosophical bent ultimately meant he could never find complete fulfillment within the official hierarchy, so he entrusted his sense of spontaneity and detachment to ink and paper.

Zhu Zhishan’s calligraphic style significantly influenced the development of cursive writing in the Ming and Qing eras and even into modern times. Later practitioners who studied Wang Xi, Huaisu, and Mi Fu often turned to Zhu Zhishan’s wilder cursive vibe for inspiration. His nuanced handling of brush speed, ink saturation, and composition remains instructive for subsequent generations.

What is more, Zhu Zhishan’s story illustrates an alternative path taken by literati of the Ming when denied success in imperial examinations: devoting a lifetime to art. Like the “romantic scholar” reputation of Tang Yin, Zhu Zhishan’s anecdotes have long fascinated the public. Beyond these colorful tales, however, his devotion to the perfection of calligraphy and his pursuit of spiritual autonomy are both aspects worthy of our admiration and reflection.

As one of the most representative calligraphers of the mid-Ming period, Zhu Zhishan excelled in regular script, running script, and cursive script alike. He integrated the spirit of the “Two Wangs,” along with the legacies of the Tang, Song, and Yuan masters, and, by combining his own flamboyance with profound technical skill, forged a style that is graceful and unrestrained. From the dignified precision of Chu Shi Biao to the unconstrained vitality of Cursive Poetry Letters Roll (《草书诗翰卷》), Zhu Zhishan deftly navigated the tension between tradition and individual flair, between formal rigor and creative freedom.

His works remain highly esteemed not merely for their technical prowess but for the genuine personality and integrity they embody. His life reflects the predicament of Ming scholars trapped in an unsatisfying bureaucratic system who turned to art as a spiritual haven—offering a vivid model for later calligraphers. As admirers from his own time declared, “Zhi Shan’s cursive is unrivaled under heaven—surely it’s not only in the Three Wu region that fine wine reigns supreme!” This capacity for vigor without forfeiting discipline cemented Zhu Zhishan’s place not only in the Ming dynasty but throughout the history of Chinese calligraphy. Even now, we can sense within his surviving works that same boundless spirit and powerful, shifting strokes—a testament to Zhu Zhishan’s enduring charm.

This translation is an independent yet well-intentioned effort by the China Thought Express editorial team to bridge ideas between the Chinese and English-speaking worlds.