Wang Duo’s Calligraphy: A Distinctive Voice of Ink in the Late Ming and Early Qing

Ren Jingjing (任晶晶)

[Editor’s Note: Wang Duo (王铎) brings to mind a tempest sweeping across the late Ming era: in a time of turmoil, he wielded his brush with reverse strokes and bold sweeps, venting his inner conflicts and anxieties. Building on the established traditions of model-script (tiexue), he nonetheless dared to innovate, arriving at a style that is at once unrestrained yet disciplined, wild yet touched by elegance. From his works, we perceive not only the cultural grounding of the literati but also the pulse of his era and the cries of the individual. Within Ming-dynasty calligraphy, Wang Duo stands as a key figure in guiding model-script toward a more personal mode of expression and as someone who opened new possibilities for Qing and later generations of calligraphers.

In today’s diversified aesthetic climate and spirit of innovation, there remains a call to draw inspiration from Wang Duo’s brushstrokes. As contemporary society undergoes its own transformations, a present-day calligrapher must both uphold the essence of model-script tradition and possess the boldness to confront the times and articulate the self. Judging from Wang Duo’s personal experiences and artistic practice, the essence of art may well be this ability to respond to one’s moment in history by branding a unique mark in each stroke.

Wang Duo’s life was destined to leave an indelible mark on the history of calligraphy. While his political positions and personal character have provoked controversy, we cannot deny his contribution to later developments in the field. Revisiting his brushwork today, we still discern the free-spirited energy of an unsettled age. Indeed, therein lies the most stirring aspect of art itself: in the black-and-white interplay of ink and paper, we glimpse the glimmer of human life and the waves of an era. If we study and observe diligently, we may, within the fervor and sorrow of his pieces, touch the late Ming world—an age of impending storms and blazing passion. In this way, Wang Duo’s ink traces bridge centuries to converse with posterity, shining as an inextinguishable beacon in the vast current of art.]

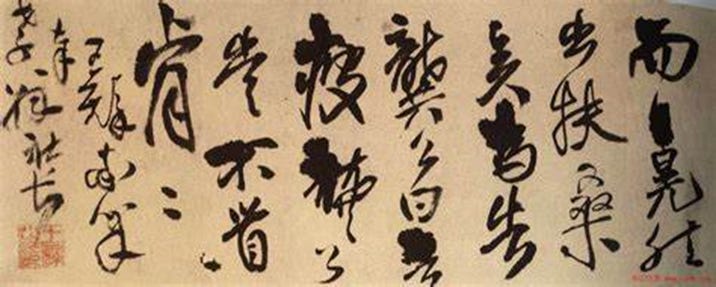

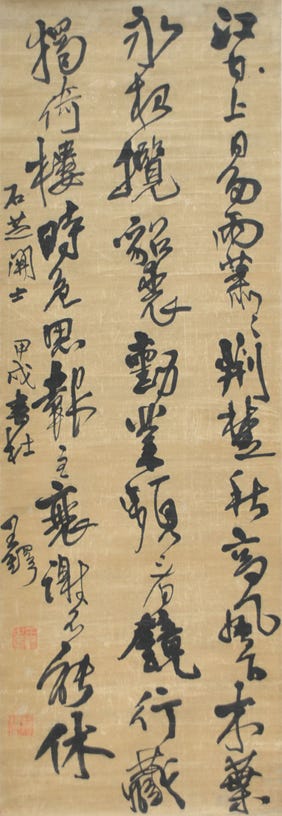

In the late Ming and early Qing calligraphy scene, Wang Duo (王铎, 1592–1652) was renowned for the bold, dashing quality of his brushwork and for a style distinctly his own. Alongside Dong Qichang (董其昌), Zhang Ruitu (张瑞图), and Huang Daozhou (黄道周), he was later counted among the four major calligraphers of the late Ming. Yet he carved out a uniquely independent path with his highly personalized brushstrokes and profound grounding in model script. Observing the numerous surviving works he left behind—running script, cursive letters, letters on fans, rubbings of inscriptions—we sense the anxiety that beset literati in those troubled times, as well as his inheritance and transformation of traditional classics. In what follows, this article will systematically explore Wang Duo’s historical context and personal circumstances, the lineage of his calligraphic tradition, the techniques and aesthetic hallmarks of his brushwork, its strengths and weaknesses, his standing in the history of calligraphy, and the significance of his work for contemporary practitioners.

Era and Personal Circumstances

Wang Duo was born in the twentieth year of the Wanli reign (1592), during the mid-to-late Ming dynasty. The late Ming period was beset by internal upheaval and external threats—eunuch domination, factional disputes among the Donglin party, rebellions like the White Lotus, and the rise of Later Jin (the Qing)—all of which brought the imperial court to the brink. Amid such turbulence, the literary and calligraphy worlds often witnessed a potent mix of nostalgia and reform-minded zeal. In an unstable political climate, men of letters held lofty aspirations yet felt suppressed, with nowhere to voice their frustrations. Many turned to pen and ink as a channel for private emotion, consolation, or release, and Wang Duo was a quintessential example of this tendency.

Born into a family of officials, according to the Chronicles of Wang Duo (《王铎年谱》) and related sources, he inherited a solid family tradition and benefited from relatively privileged schooling. His father, Wang Bi (王璧), served in government, and the family placed great emphasis on poetry, literature, and calligraphy, laying a firm foundation for Wang Duo’s later scholarly and artistic achievements. In his youth, he studied Confucian texts and entered officialdom through the imperial examinations, serving posts both locally and at court, eventually attaining positions such as Minister of Rites and Minister of War. Whether at the exams or in government, he distinguished himself through remarkable literary talent, which won him social acclaim but also embroiled him in numerous political vicissitudes.

When the Chongzhen Emperor took his own life, Li Zicheng took Beijing, and the Qing army advanced south, Wang Duo’s life shifted dramatically. In an era of persistent warfare and unrest, scholars were generally enveloped in apprehension and anxiety. For Wang Duo, these events stirred a deeper lament: “the body may drift with the current, yet the heart remains mindful of the old realm.” After the Qing army entered the Pass, Wang Duo chose to serve the new dynasty, an action that sparked much criticism at the time. He thus served both Ming and Qing, undergoing enormous psychological upheaval and moral self-examination. He himself must have been torn with conflicting feelings, bearing the burden of ethical and personal convictions. The Qing’s policies of cultural reformation aimed at Han officials only increased his sense of being stifled. In such a vortex of complexity, he needed a way to channel his turmoil, and calligraphy became his crucial means of solace.

In the early Qing, though briefly occupying official posts, Wang Duo could not shake his inner conflict and pain; hence, he increasingly expressed himself through brush and ink. The turbulence of his era and his own internal struggles are readily apparent in his running-cursive works: strokes that rove like lightning, conveying unrest and desolation. His brushwork did not slacken in the least under the new regime but instead grew more uninhibited, as if through radical calligraphic expression, he aimed to voice an anxiety unutterable in words. Freed by the act of writing, he allowed his emotions to flow across the paper. One might say that this historical backdrop, combined with personal travails, ultimately shaped Wang Duo’s singular style in the late Ming. Behind that defiance lay a deep melancholy shared by late Ming scholar-officials—“scholars with no way to serve their country”—and from this sprang the explosive power manifested in his calligraphy. Such potent feeling infused his brush, imprinting the late Ming calligraphic tradition with a characteristic “majestic austerity, tinged with sorrow.” His script often unfurls with “sweeping intensity, a gale-like force,” the outcry of a solitary literatus amid chaos.

The Sources of His Style and Its Lineage

Taking Inspiration from the Two Wangs: The Continuation of Model-Script

In the Ming era, model-script (tiexue) flourished, and educated gentlemen regarded immersion in the legacy of “the two Wangs” as the highest principle. Wang Duo was no exception. He was deeply influenced by Wang Xizhi (王羲之) and Wang Xianzhi (王献之), echoing their approach in his brushstrokes, character structures, and the technique of pushing in and out with the brush (“nei nie, wai tuo”). Notably, in his running and small-cursive works, the influence of the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion (《兰亭序》), Sage Teachings (《圣教序》), and First-Moon Letter (《初月帖》) often appears. For instance, he frequently employed a relatively fine, resilient center-tip stroke, with subtle shifts in pressure and linking strokes between characters so delicate they look like “filaments” connecting them, creating a cohesive rhythm throughout.

Drawing on the Techniques of Song, Yuan, and Ming Masters

From the mid-Ming onward, model-script no longer confined itself to the rigorous Tang-dynasty style but instead tended to assimilate elements from Song and Yuan masters. Building on the framework of the two Wangs, Wang Duo absorbed the essence of Su Shi, Huang Tingjian, Zhao Mengfu, Wen Zhengming, Dong Qichang (董其昌), and others. He was especially drawn to Dong Qichang’s graceful, animated flair and his refinement of the spirit of the Jin dynasty. At the same time, he also took note of Zhang Ruitu’s energetic tension and dynamic strokes. In blending the achievements of Song and Yuan calligraphers, Wang Duo at times displayed a free, unbound flourish and a clever coarseness within refinement, achieving a balance of ancient elegance and fresh expression.

Incorporating Stele-Style Calligraphy and Forging a Personal Breakthrough

Although Wang Duo’s work largely belongs to model-script, he was not altogether dismissive of the robust force found in stele-style calligraphy. Late Ming intellectual life encouraged experiments in copying such inscriptions as the Stele of Zhang Menglong (《张猛龙碑》) or the Stele of Lord Zheng Wen (《郑文公碑》). While no records explicitly confirm systematic study of Northern Wei steles by Wang Duo, his larger running-cursive works display occasional stele-like traits, including squared corners in vertical strokes, pointed or sharply angled endpoints, and horizontal strokes with edges of tension, lending a sense of powerful momentum. The fusion of stele- and model-script elements endows his pieces with a visual impact that is “tilted yet controlled, vigorous, and exhilarating.”

Characteristics of Wang Duo’s Calligraphic Style

Brushwork: Reverse Strokes and an Unbridled Spirit

Wang Duo’s brushwork is distinguished by reverse-angled starts and quick lifts, instantly imbuing each stroke with tensile force. He often pivots the brush fibers to create sudden, dramatic changes of direction that intensify every turn. In his running cursive, initial strokes typically carry a reverse thrust, while final strokes may be light and airy or dashed off with a hint of dry brush. Sometimes he elongates a stroke to extremes, sometimes he abruptly halts, opening and closing in broad gestures that generate a sense of rhythmic variety. This fosters an electrifying energy reminiscent of a fierce wind sweeping across the earth. The feeling of “order in apparent haste” reveals his profound mastery of the two Wangs’ controlled up-and-down motion, as well as the late Ming literati’s newly liberated individuality.

Structure: Varied Angles and a Flexible Center of Gravity

In structuring characters, Wang Duo relished departing from conventional formations, upholding “there must be method in the idea, yet no method must be fixed.” He often uses angled postures to accentuate movement, such as horizontal strokes that rise diagonally or plunge straight downward, with vertical strokes occasionally rugged, occasionally taut. These seemingly casual shifts are, in fact, carefully considered so that each character corresponds to the next through slender connecting strokes, forming an overall rhythm. Meanwhile, he arranges the flow of lines in a manner akin to “introduce, develop, turn, conclude,” sometimes rushing, sometimes lingering. The entire piece gives the impression of “a dragon soaring among clouds, unstoppable in its momentum.”

Ink Tones: Alternating Dry and Wet, Layered in Complexity

Wang Duo’s use of ink typically appears generous and substantial, yet not without subtle dryness and moisture. Because he writes with great speed, the ink on the brush may not fully saturate before meeting the paper, resulting in streaks of dry-brush or near-transparent passages in the middle or tail of a stroke, heightening textural layers. Occasionally, he slows his pace to load the brush more completely, allowing certain strokes to appear darker and more substantial. The contrast of “thick ink” and “flying white” not only enriches the surface but also reinforces the sense of bold spontaneity.

Composition: Interwoven Echoes and Daring Innovation

Wang Duo’s arrangement of spaces often flows with an unstudied air of freedom. Many letters, though casually written, exhibit an artful compositional intelligence. Lines respond to one another, deftly staggering the vertical alignment of characters so that the entire piece unfolds like “water and clouds seamlessly joined” or “rivers and mountains surging forth.” Especially in grand cursive or wild cursive writing, he ventures into extremely tilted forms and dense clusters of strokes, seeking “stability in daring, movement in sweeping force.” Some have remarked that he “frequently disregards conventional rules, yet invariably remains in accordance with them,” perfectly capturing his bold use of layout.

Emotional Expression: The Hand of the Literatus in Every Stroke

Late Ming sociopolitical upheaval and Wang Duo’s personal fortunes steeped his creations in poignant emotion. On the one hand, he had passed the imperial examinations and held grand ambitions; on the other, the downfall of the Ming and the ascendancy of the Qing cornered him into a difficult moral dilemma. This internal conflict is repeatedly unleashed in the intense feeling pervading his lines. At times, each stroke brims with movement; at others, it is as weighty as a mountain, rising and falling so that we glimpse an isolated scholar in a time aflame with chaos, grappling with anguish. Tuning in to the spirit behind his brushstrokes enables a deeper understanding of Wang Duo’s calligraphic vision.

Strengths: Unfettered Grandeur and Diverse Roots

Wang Duo’s work integrates Jin-dynasty model-script with Song and Yuan influences, while also absorbing the strengths of contemporaries like Dong Qichang, ultimately forging his own signature style. His brushwork stands out for its energetic sweep, his character structure for its angled variation, his composition for its airy elegance, and his ink usage for its rich layers. These features confirm a mastery achieved in both technique and artistry. Equally noteworthy is his ability to merge personal feeling with the spirit of the times, investing his pieces with a genuine vitality.

Weaknesses: Overly Rapid Execution or Excessive Fiery Tone

Any calligrapher seeking to defy convention and develop a personal style may encounter shortcomings. In Wang Duo’s case, the swift zeal of his brush sometimes leads to less stable handling of ink, with certain strokes appearing shaky or fractured, compromising the overall cohesion and fullness. There are moments when his running cursive seems excessively “fiery,” leaving viewers to sense an over-aggressive energy or a lack of inner softness—a possible reflection of late Ming restlessness. These minor flaws underscore both the intensity and slight impulsiveness of that era’s artistry.

Position in Ming-Qing Dynasty Calligraphy

From Model-Script to Personal Expression in the Late Ming

Throughout the Ming dynasty’s calligraphic evolution—from the staid official style of the Grand Secretariat to the refined elegance of the Wu School, then on to the bold reinventions of Dong Qichang, Zhang Ruitu, Wang Duo, and others—a visible arc emerges, shifting from strict adherence to model-script toward greater license for personal expression. Wang Duo, both a stalwart of model-script and a fearless innovator within the “two Wangs” framework, bridged past and future, cultivating a flamboyance in late Ming that resonated as something entirely new. Studying his pieces reveals how model-script traditions could be transformed amid sociopolitical upheaval into something fresh and dynamic.

Mentioned in the Same Breath with Dong Qichang, Zhang Ruitu, and Huang Daozhou

A phrase widely cited in late Ming circles was “the south has Dong, the north has Wang,” referring to Dong Qichang and Wang Duo as comparably eminent calligraphers with distinctly divergent styles—Dong Qichang, refined and measured; Wang Duo, exuberant and carefree, with a more potent emotional undercurrent. Comparing him to Zhang Ruitu, one sees that Wang Duo more rigorously maintains a foothold in tradition, whereas Zhang ventures further into unconventional territory. Meanwhile, Huang Daozhou’s vigorous, lofty style also finds its place alongside Wang Duo. These four figures, with their contrasting aesthetics, created a kaleidoscopic panorama of late Ming calligraphy, collectively marking a peak moment in the art’s multiplicity.

Influence on the Qing and Later Calligraphy

Though Wang Duo lived through the transition from Ming to Qing, his calligraphy continued to inspire Qing-dynasty practitioners. For example, Qing masters of stele-style such as Deng Shiru, Zheng Fu, and Yi Bingshou did not entirely reject model-script, and some of the dramatic compositional devices and daring strokes trace their roots to Wang Duo’s experiments. In the late Qing and Republican eras, calligraphers like Zhao Zhiqian and Wu Changshuo, who balanced stele- and model-script approaches, likewise drew from the dynamism of late Ming figures like Wang Duo. Thus, one can rightly claim that Wang Duo played a critical transitional role during this pivotal shift in calligraphy.

Lessons for Today’s Calligraphers

Study the Ancients but Avoid Blind Imitation

Wang Duo’s achievements hinged on his profound familiarity with the classical model-script of the two Wangs. For contemporary students of calligraphy, copying the classics remains an indispensable step, yet mere replication is insufficient. After thoroughly grasping the old masters’ rules, one must re-create anew. Wang Duo adhered to tradition but also infused it with his individual flair, exemplifying an approach of “respecting established methods but capable of transcending them”—a stance that remains instructive today.

Dare to Innovate in Turbulent Times or Periods of Change

Wang Duo lived through a great upheaval at the close of the Ming and start of the Qing. He fused outward societal tumult with an inward artistic drive to “innovate.” Though today’s world differs markedly from his, ours, too, is an era of rapid change. For an artist, finding a way to merge contemporary shifts with personal reflection, elevating both in one’s brushwork, is a pursuit worth serious contemplation. Only by risking new territory and defying convention can one forge new ground in calligraphy.

Emphasize Emotional Resonance and Personal Character

What renders Wang Duo’s calligraphy so moving is the infusion of individual feeling and temperament into every stroke. Calligraphy is not merely technique upon technique—it is the outer reflection of inner character and spirit. Anyone seeking to produce work that touches the heart must cultivate sound learning and genuine emotion, approaching the brush as an expression of selfhood rather than an exercise in technical prowess.

Balance Tradition and Breakthrough

One should draw on tradition without remaining trapped by it and develop a personal style without succumbing to eccentricities for their own sake. Wang Duo’s ability to emerge as a truly original figure among countless imitators owes much to his precise balancing act between tradition and individuality. In contemporary calligraphy, extremes—whether in forced novelty or in dogged conservatism—veer away from the essence of art. The most valuable lesson Wang Duo offers is the notion of honoring the past without being confined by it, all the while uniting the spirit of the times with one’s own aspirations. This, in turn, yields calligraphic works endowed with singular worth.