The Exploration and Return of Tu Xinshi’s Calligraphy

—Reading the Calligraphy of Tu Xinshi in Returning Home (回家)

By Wu Shan

Tu Xinshi, also known by his pen names Tu Hao and Chuanliu, is a Chinese calligrapher born in 1950 in Suzhou, with ancestral roots in Shaoxing. He began studying calligraphy under master Hu Wensui in the late 1960s, developing his skills over more than a decade. In 1982, he joined the Shanghai Calligraphers Association. After working as an editor in Shanghai, he moved to the U.S. in 1987 and earned a master’s degree in sociology. Tu became a bridge between Chinese and American cultures through his founding of the Sino-American Post (1994) and the Rocky Mountain Chinese Calligraphy Association (1995). Since 1997, he has taught calligraphy at universities in Colorado, guiding over 600 students. He held a major solo exhibition in Beijing in 1998 and co-founded the Denver Confucius Calligraphy Classroom in 2007. Tu has served as president of the American Society for Calligraphy Education and holds academic posts in China, including at Peking University. He is a member of the Chinese Calligraphers Association and Vice Chairman of the National Committee for Chinese Painting and Calligraphy Arts. His works are held in major institutions, including the Denver Art Museum, the National Museum of China, and the National Art Museum of China.

In today’s flourishing cultural atmosphere of a growing “calligraphy fever,” the question of how to merge the inner spirit of traditional Chinese calligraphy with the aesthetic demands of contemporary society remains a topic that warrants constant reflection and response. In the spring of 2025, the individual known as a “People’s Art Representative,” Mr. Tu Xinshi (屠新时), held an exhibition in Shanghai under the theme Returning Home (回家). Drawing upon decades of dedicated work in cursive script and enriched by his cross-cultural teaching experiences overseas, he presented his profound understanding and enthusiasm for the art of calligraphy. Born in Suzhou and originally from Shaoxing in Zhejiang Province, yet long residing in the United States, Tu Xinshi’s artistic journey closely resembles his cursive style: at times gracefully carefree, sweeping across the paper; at others succinct and measured, resonating with lingering depth. His creative and promotional pursuits are not merely a record of a life steeped in brush and ink but also a fine tale of Chinese calligraphy’s international dissemination.

From Tradition to Contemporary Leaps

When discussing the course of Tu Xinshi’s calligraphy, one must mention his mentor, Hu Wensui (胡问遂). In the late 1960s, a young Tu, introduced by his great-uncle, visited Hu Wensui—who was then living in Shanghai—and thus entered a master-apprentice relationship between two natives of Shaoxing, bound by familial affinity. Renowned as one of the “pioneers of modern calligraphic reform,” Hu was known for his deep expertise and his teaching philosophy of “individualized instruction, attentive to each student’s strengths.”

Under the guidance of such a master, Tu built a solid foundation in stroke and character composition. Hu emphasized the “lift-press-turn” motion of the brush hairs and required repeated drills in the four main techniques of “speed, lift, pause, turn,” ensuring that each student fully experienced the tension and momentum in their brushwork. In calligraphy study, one must not only master the structure of each individual character but also learn to integrate white space and black ink, row, and column, aiming for a flowing cadence of energy and a clear, lively rhythm throughout the composition. Within Hu’s lineage, the spatial rhythm of traditional copybooks, the classical style of the Jin and Tang dynasties, and the evolution of the Ming and Qing periods all intermingled, championing “studying the ancients without slavishly adhering to them.” Immersed in these classical methods while still young, Tu also began to cultivate an awareness of fusing traditional brush and ink with the modern context.

Cursive script is the most expressive and emotive form of calligraphy, yet also the most challenging. Without sufficient technical grounding and sustained practice with classical models, it is difficult to produce cursive work that conveys both inner structure and aesthetic meaning. Tu has often spoken in various settings of his admiration for the Two Wangs (Wang Xizhi [王羲之] and Wang Xianzhi [王献之]) and for Mi Fu (米芾). Over the years, he regularly copied classic works such as the Letters of the Two Wangs (二王帖) and Mi Fu’s Shu Su Tie (米芾蜀素帖), while also drawing inspiration from The Treatise on Calligraphy (书谱) by Sun Guoting (孙过庭) and The Autobiographical Essay (自叙帖) by Huai Su (怀素), absorbing the essence of celebrated cursive pieces throughout history.

As Wu Weishan (吴为山) once put it, Tu’s brushwork is “bold and vigorous,” reminiscent of Mi Fu’s “sweeping velocity.” When his brush travels across the paper, its speed is lively, with a dance-like sense of movement in each lift and drop. The strokes can be so powerful they penetrate the paper, and yet, in more ethereal passages, they are controlled with ease.

Traditional cursive script values the unity of mind and hand, the seamless flow of energy, and the aesthetic principle of completing a work in one unbroken burst of movement, highlighting the calligrapher’s personal spirit. One can sense this quality in Tu’s compositions: when he writes the poetry of Du Fu (杜甫), Han Yu (韩愈), or Tao Yuanming (陶渊明), the brushwork often conveys the melancholic depth or airy grace of the text, allowing viewers to experience the interplay between word and artistic atmosphere.

Through years of diligent practice and close observation, Tu established a cursive style that is rooted in the elegance of the Jin Dynasty, softened by the free-spirited touch of the Song. Mi Fu once spoke of “sweeping strokes,” confidence and freedom in his brushwork that merges naturally with the refined “Two Wang spirit” of the tradition. For Tu, “taking the highest standards as one’s model” means being grounded in the most authentic spirit of Chinese calligraphy without indulging in trendy exaggerations.

Still, should one merely stay within the traditional framework of brush technique, it becomes difficult for calligraphy to gain fresh vitality in today’s context. Meeting face-to-face with audiences from various cultural backgrounds during his many international exhibitions and in university classrooms where he taught American students to write with a Chinese brush, Tu gradually discovered how the cursive script’s “stage of lines” resonates with the “abstract expression” of contemporary art. American students are often amazed by the “unbridled linework” and “rhythmic structure,” yet they also need deeper cultural bridges to appreciate the symbols behind those lines.

This reflection led him to experiment moderately with structural distortions, spacing, and ink shading in his cursive works, aiming to create an artistic effect with a certain sense of “space.” For example:

In works like Heavenly Questions (天问) and Thoughts on the Vastness of the Nine Provinces (思九州之博大), he intentionally elongates some brushstrokes, using the open gaps between running script or cursive characters to establish a strong visual contrast, forming a dynamic clash between energy and momentum.

Traditionally, cursive emphasizes the interplay of dry and wet, focusing on linework. Yet Tu sometimes applies heavier ink in certain parts of a character or adds extra strokes, allowing the layered interplay of dark and light to echo a Western painting technique akin to “chiaroscuro.”

When viewers take in the work as a whole, they may sense the rises and falls of a musical piece. Certain strokes might suddenly lighten or be firmly pressed, akin to a variation or crescendo that punctuates a musical movement.

These explorations of technique have not come about overnight; rather, they are the fruit of Tu’s decades-long immersion in teaching, research, and exhibitions. He has absorbed modern aesthetics through an international lens while always returning to the roots of “traditional brush and ink.” As he likes to say, “Never forsake the fundamentals of brush technique, but constantly think about how to help people genuinely feel the power of these lines.” This is why connoisseurs detect echoes of ancient tradition in his cursive script, while newcomers are struck by its sweeping visual impact.

The Sentiment Behind the “Returning Home” Journey

In the spring of 2025, Tu returned to Shanghai to stage an exhibition of calligraphy under the theme Returning Home. As he wrote in his exhibition preface, it was both an homage to his mentor, Hu Wensui and a heartfelt tribute to the land that nurtured his dream of calligraphy. Along with many recent masterpieces in cursive, the show presented documentation of his overseas teaching, including rare photographs and student works. These diverse materials gave the public a multilayered glimpse into a life in calligraphy that transcends time and space.

Hailing from both Shaoxing and Shanghai, Tu explained that Returning Home felt like an occasion of “gratitude and report”: gratitude for Hu Wensui’s painstaking instruction years earlier and for the soil that fostered his calligraphic culture. Visitors to the exhibition could see numerous precious photographs of him with Hu, as though that esteemed elder of the calligraphy world were still quietly observing his student’s unfolding creative universe.

At the same time, “going home” signifies a deeper “spiritual return” for an artist who has spent extensive periods abroad. Throughout his international exchanges and cross-cultural teaching, Tu came to realize that Chinese calligraphy stands as one of the core symbols of Chinese civilization. Presenting an exhibition in Shanghai now is undoubtedly an expression of “what I have learned, realized, and gained”—a way of giving thanks. Inevitably, the artist’s profound homesickness reveals itself in the ink on paper.

Within the exhibition pieces, visitors can appreciate his refined renderings of classical poetry while also discovering some works on modern themes. Even more significant are the displayed works by his foreign students, which underscore a message of “cultural blending”: these students pick up the brush and dip it in ink to write Chinese characters—some upright and measured, others more relaxed—featuring short verses or self-composed combinations of characters. Their works brim with a distinct creative vitality.

In a sense, this method of “transmitting culture through calligraphy” aligns with the broader hope that “Chinese calligraphy will reach the wider world.” From Returning Home onward, Tu exemplifies not only the gratitude of a Chinese calligrapher living in the United States toward his homeland but also the conviction of “bringing Chinese calligraphy onto a more expansive stage.”

At the Returning Home exhibition, many visitors were drawn not only to the sweeping force of his cursive lines but also to the wealth of documentary photographs: glimpses of his overseas teaching, moments of collaboration with eminent figures, and certifications from various international exhibitions. These records chronicle more than three decades of unwavering dedication, signposting the trajectory of Chinese calligraphy’s incremental global presence. Contemplating these images and works, a young college student wrote in the visitor’s book: “To see his brushwork is to sense the fragrance of learning; to see his footprints is to gain confidence.” Perhaps this also encourages anyone devoted to the pen today: the road of calligraphy is not confined to lamentations of a single time or place; it merges with the broader currents of cultural exchange, igniting ever more profound emotional resonance and spiritual awe.

From “Cursive Exploration” to “Spiritual Homecoming”

Looking over the decades of effort that Tu has poured into brush and ink, one can see how he has remained steadfast on the path of cursive script, balancing a reverence for tradition with an openness to converse with contemporary art forms and cross-cultural perspectives. His experience of living abroad and traveling back and forth between two worlds has allowed him not merely to “write” a path that bridges East and West but also to “walk” into a distinctive legacy for the international promotion of calligraphy.

Cursive script is often deemed “the pinnacle of calligraphic expression,” for it most directly captures the calligrapher’s spirit and personal vision. Tu’s cursive has been widely acclaimed and collected, receiving recognition on international stages, largely because he succeeds in fusing the profound legacy of classical calligraphy with the dynamic impulses of modern aesthetics. His brush may sometimes surge like a dancer ablaze with passion, while at other times, it retreats into reserve, evoking the essence of the Jin and Tang. He does not chase novelty for its own sake; rather, an authentic rhythm emerges in the gentle flow of his lines.

When he returned to Shanghai in 2025 to host the Returning Home exhibition, he paid tribute to his mentors and cast a hopeful gaze toward the future. In front of his friends, family, and local audience, he presented a body of thoroughly mature cursive work and a wealth of teaching achievements, offering a testament to his long-standing international efforts to champion Chinese culture. Such a “homecoming” transcends mere geography to become a heartfelt reunion with his own cultural bloodline. The vivid cursive pieces serve as a wordless dialogue between artist and homeland, between nation and the world—brush and ink becoming the medium, sentiment becoming the bridge, inviting viewers to feel a profound sense of belonging and cultural identity within the dance of the lines.

For today’s enthusiasts and scholars of calligraphy, Tu’s story offers multiple insights: solid erudition and technical grounding always form the bedrock of artistic innovation; one must revere tradition and strive to discover new meaning in a modern framework; and in promoting calligraphy abroad, success requires true openness and the willingness to engage in dialogue on an equal footing. By following this course, cursive calligraphy—one of China’s unique artistic forms—may radiate an even greater splendor.

Within the fluid lines of cursive script lies the pulse of an ancient civilization, echoing the universal language of world art. Tu’s Returning Home exhibition reaffirms the robust vitality of this classical art: deeply nourished by its traditional wellsprings, yet ever able to absorb fresh energy across borders. The cosmos of ink and brush is vast, and its human sentiment likewise. Indeed, the path of cursive script has always been one of inclusiveness and fluid creativity. Through Tu’s work and the footprints he has left behind, we glimpse a calligrapher driven by wholehearted passion and a facilitator of dialogue between Chinese and Western cultures.

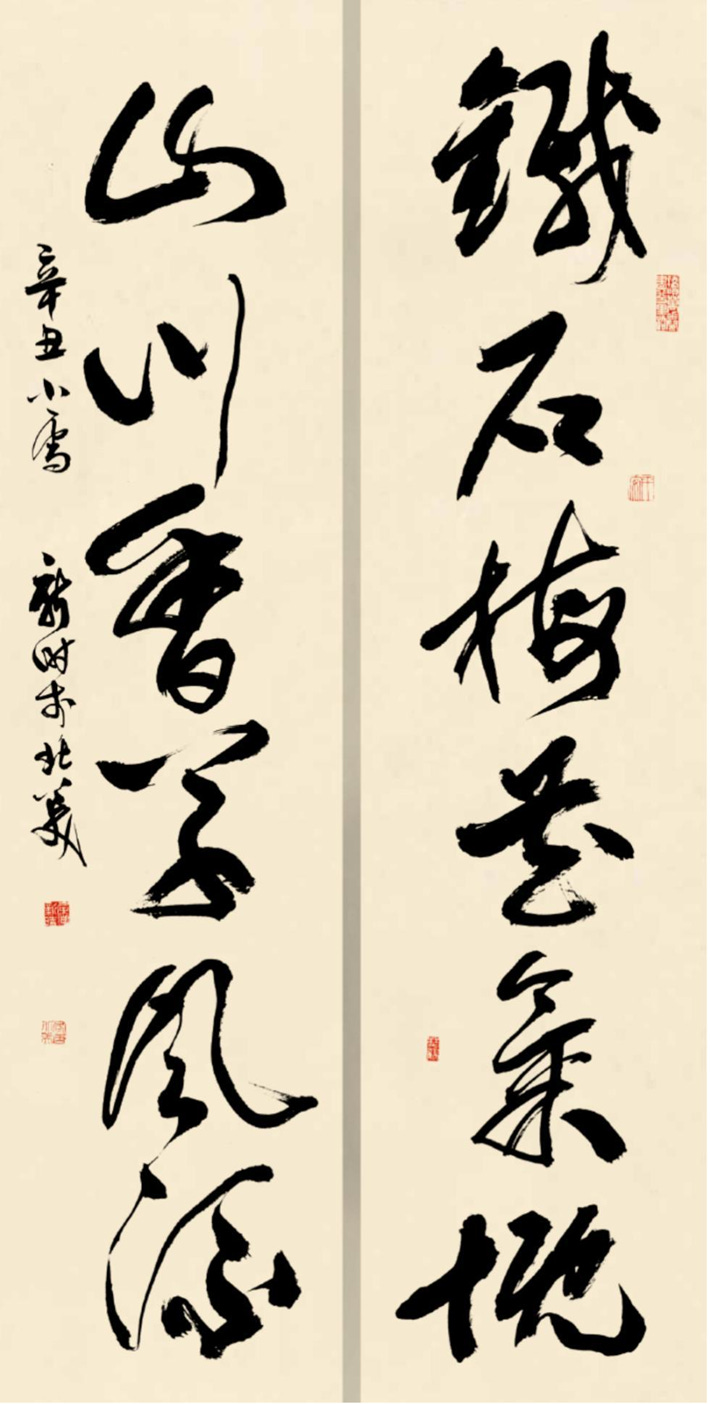

Returning Home may be but one chapter in the ongoing scroll of his life. The chapters yet to unfold will surely be authored by Tu and all who care about Chinese calligraphy. In this cultural renaissance, steadily gathering momentum, we look forward to more calligraphers like him, blending the soul of tradition with the power of the present, forging bonds between emotion and civilization through the written line. This is how we truly realize the aspiration that “the spirit of iron and stone meets the fragrance of plum blossoms, the charm of mountains and rivers”―opening new vistas with each brushstroke while preserving the roots that gave it life. As one of his notable cursive works proclaims, “Ponder the vastness of the Nine Provinces and transcend all boundaries,” so too will Chinese calligraphy’s immense territory and boundless potential continue to be upheld, reimagined and rekindled by calligraphers like Tu Xinshi.