Melding Tradition and the Present, Establishing a Unique Style—An Appraisal of Shen Xinde’s Small Xing-Kai Calligraphy

承古融今,独树一帜 —沈新德小行楷书法评述

By Li Xiaoping (李晓平)

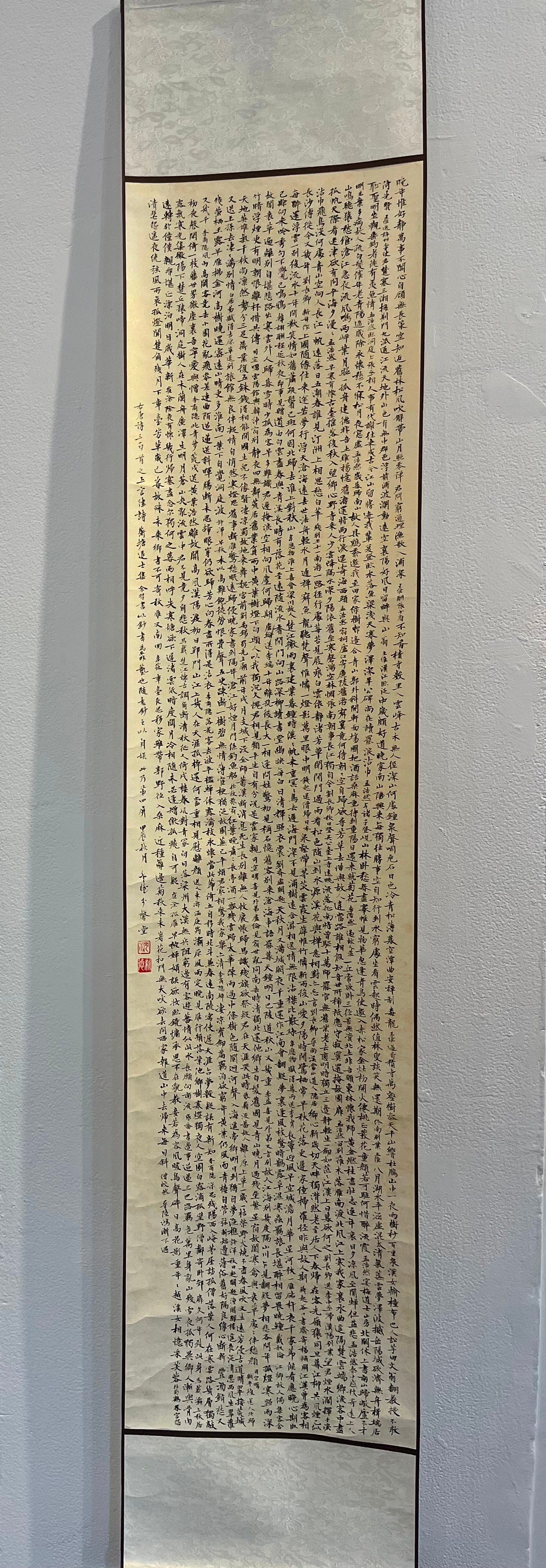

【Editor’s Note: Shen Xinde’s small xing-kai calligraphy masterfully blends tradition with modern sensibilities, drawing from the legacies of Zhao Mengfu, Wang Xizhi, and Mi Fu while forging a distinct personal style. His work maintains the stability of kaishu while embracing the fluidity of xingshu, achieving a balance of grace and precision. Shen refines classical techniques through nuanced adjustments in stroke rhythm, spacing, and ink variation, enhancing the dynamic interplay within and between characters. His calligraphy embodies an introspective literati spirit, merging textual and visual artistry to create a harmonious aesthetic. In an era where calligraphers must navigate between heritage and innovation, Shen’s approach exemplifies a path of deep study, selective adaptation, and disciplined execution. His work not only preserves the elegance of traditional small script but also expands its expressive potential, offering valuable insights for contemporary calligraphers seeking to balance historical reverence with creative evolution.】

In the increasingly diverse landscape of contemporary calligraphy, it is rare to see an artist create something genuinely fresh while remaining grounded in the profound traditions of the brush and ink. A close look at Shen Xinde’s (沈新德) small xing-kai works makes it clear that he has drawn extensively on classical sources and reimagined them with distinctive individuality. Here, I attempt to synthesize the brush-and-ink spirit reflected in his oeuvre, compare it to related masterpieces of antiquity, and explore the main lineages he inherits, the stylistic features and breakthroughs he achieves, and the aesthetic significance his work holds for the modern calligraphy scene.

Continuing the Tradition: Origins and Comparisons (承继传统:脉络与比较)

Small xing-kai (小行楷) combines the fluidity of xingshu (行书) with the upright structure of kaishu (楷书) in a relatively smaller script form. Compared with larger characters, it places greater emphasis on the delicate control of brushstrokes and composition, as well as on the artist’s personal cadence and the dynamic of lifting and pressing the brush. Historically, when it comes to smaller script or xiaokai (小楷), we can trace it back as early as the era of Zhong Yao (钟繇) and Wang Xizhi (王羲之). Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi (王献之), followed by calligraphers such as Zhiyong (智永), Yu Shinan (虞世南), Ouyang Xun (欧阳询), and Chu Suiliang (褚遂良), not only established the fundamental paradigms for xingshu and kaishu, but also laid the groundwork for subsequent developments in small script. By the Song and Yuan dynasties, Su Shi (苏轼), Huang Tingjian (黄庭坚), Mi Fu (米芾), and Zhao Mengfu (赵孟頫) took the fluidity of xing-kai in varied directions, giving small xing-kai a dual character that retained the firm skeleton of kaishu while capturing the graceful movement of xingshu.

In more recent times, many calligraphers have inherited the “tiexue” (帖学) tradition of Wang Xizhi and Zhao Mengfu, but those truly capable of merging “ancient spirit” with “modern verve” usually make breakthroughs by fusing multiple aspects of brushwork, character construction, spatial arrangement, and literati sensibility. Shen Xinde’s small xing-kai reflects a deep absorption of the tiexue lineage—particularly from Zhao Mengfu and Mi Fu—while also drawing on a broad field of classical resources, including the dynamic energy of Mi Fu’s brush and the meticulous elegance of Wen Zhengming (文徵明). The result is a calligraphic style uniquely his own.

From Shen’s small xing-kai, one readily sees how he borrows from both Zhao Mengfu and Wang Xizhi. On the one hand, his strokes possess a “steadiness without rigidity, grace without fragility,” echoing Zhao Mengfu’s emphasis. You can detect a reserved handling of the brush tip in the opening and closing strokes, where each line is fully formed; the horizontal strokes, as well as the left and right slants, often feature subtle “returning brush tips,” demonstrating a consistent commitment to using the central tip. At the same time, he does not slavishly adhere to the rounded, polished feel of Zhao’s style, occasionally allowing sharper turns, which adds a dash of vibrancy to an otherwise solid framework.

On the other hand, in comparing his work to that of Wang Xizhi, Wang Xianzhi, or other masters of the Jin era, Shen’s small xing-kai may not always reach the lofty ideal of “unfettered and far-reaching, contained yet airborne.” Still, in his execution, you often see energetic shifts between pressing and lifting or varying speeds of brush movement. Notably, the vertical strokes and pivotal turns sometimes carry an inward tension, hinting at his appreciation of Jin and Tang-era methods. Yet he intertwines these classical techniques with a distinctly modern briskness, reducing overly extended connecting lines between characters while strengthening the sense of interplay among individual characters. This approach yields a measured density and an appealing clarity throughout the work.

Structurally, small xing-kai is easily marred by excessive slickness or looseness on one end and excessive stiffness on the other. Shen leans toward a slightly inward focus for each character, maintaining overall solidity. In contrast to small kai scripts that resemble the so-called Guange style, he does not deliberately strive for tightly stretched forms. Rather, he balances horizontals and verticals—varying lengths and sometimes introducing diagonal elements—with a nuanced touch. The resulting composition is orderly yet retains the spirit of xingshu. It is this calibration of “micro-adjustments” that produces a uniform yet rhythmically engaging matrix across the page.

Calligraphic Lineage: Blending Tradition and Present (书风渊源:承古融今)

Zhao Mengfu (赵孟頫) is renowned as a pivotal figure in the “revival of kaishu,” with small kai and xing-kai pieces that are admired for their warm elegance and dignified character shapes, along with a subtle sense of motion. In Shen Xinde’s brushstrokes, we see evidence of Zhao’s influence in the frequent use of “closing strokes with a returning tip,” as well as a balanced synthesis of square and round forms that exude a stable yet graceful charm. Zhao’s style advocates “levelness and containment of the brush tip,” and Shen’s handling of turns and lifts generally follows that principle, creating a profound, understated quality without any floating or drifting.

However, Zhao’s small kai—marked by a certain inward calm—sometimes appears overly sedate, lacking in spontaneity. Shen addresses this by infusing his script with his own sense of momentum and brush dynamics. He occasionally intensifies the force of the slants or accelerates the turn at the lower left or upper right corner of a character, endowing each glyph with greater rhythm and speed. As a result, his work is no longer just purely “gentle and well-proportioned” but acquires a certain “Mi Fu–like” flair of sweeping energy and pause. In this subtle tension between gentleness and vigor, one can see his effort to break the barriers between Zhao Mengfu and other tiexue traditions.

No discussion of xingshu or xing-kai can ignore the Two Wangs (二王) tradition. Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi have influenced calligraphy for a thousand years, constantly reinvented by later generations. Shen’s engagement with the spirit of the Two Wangs is evident in the starts, stops, and transitions within each stroke. His horizontal and vertical endings often show a slight return of the brush tip, and he occasionally employs minimal linking strokes to connect characters, rendering them compact but not suffocated. This flexibility—an ability to connect or separate—highlights one of the Two Wangs’ signature strengths.

Moreover, the Two Wangs’ system emphasizes the fluidity and spirit that suffuse the entire composition. While writing large characters makes it easier to showcase those linked brush movements, in smaller script, this sense of flow must be deftly allocated across strokes and character shapes. Shen accomplishes this particularly well: he refrains from excessive “one-stroke” connections or overly elaborate joinings but does not sacrifice the vitality of individual strokes just because the characters are small. Thus, each line of small xing-kai, though diminutive, still reveals how the characters echo one another, their energies connected. This continuity with the Jin and Tang tradition is unmistakable.

Breakthrough and Innovation: Seeking New Frontiers Within Tradition (突破与创新:在传统中寻新境)

Observing Shen Xinde’s small xing-kai, one notices his acute sense of “rhythm,” which aligns with modern aesthetic interests. While the ancients certainly prized proper variation in speed and pressure, contemporary calligraphy has become more sensitive to the orchestrated pacing of individual strokes. Shen frequently uses contrasts in thickness, dramatic lifts and presses, and fluctuations in brush velocity to generate a “tremor” in certain sections, like stronger and weaker beats in music, producing a palpable, rhythmic flair.

Given the smaller confines of small xing-kai, creating visible rhythmic nuance without descending into chaos demands considerable skill. Shen manages to keep the overall structure dignified yet, through alternating moments of quickness and calm, heaviness and lightness, conjures a sense of motion. In this way, his “micro-innovations” in technique signal a defining element of his personal style—an equilibrium between orderly grace and spirited expressiveness.

When considering a complete piece by Shen, one sees that he values more than the perfection of individual characters; he focuses on the interaction of each paragraph and line. Small xing-kai compositions often adopt vertical or rectangular formats. Here, the spacing between lines and the interplay between characters take on heightened importance. Compared with the traditional approach, where small kai tends to keep evenly aligned rows and tight line spacing—or certain modern small xingshu pieces that pursue ample, free-flowing negative space—Shen prefers to maintain a fairly uniform spacing between characters and lines, making slight adjustments only at key junctures. By doing so, he leaves room for visual “breathers,” enhancing the overall cohesion.

In a longer piece describing scenery or an object, he may widen the spacing in a few select lines to emphasize those passages; or when concluding a verse, he might slightly enlarge the final character, signifying closure or transition. Such structuring respects the orderly foundation of small xing-kai while adding subtle layers of visual interest, inviting readers to linger on certain sections.

In modern calligraphy, variations in ink concentration, dryness, and moisture also serve as markers of innovation. Though Shen’s small xing-kai usually features a rich, even ink tone, he occasionally introduces faint dryness or lighter strokes, merging dryness and wetness on the same line. These are never as dramatic as in bold, freehand calligraphy, but they lend depth and texture in small areas. Viewers thus witness not only the beauty of each character’s structure but also the nuanced dialogue between brush, ink, and paper. The lines remain crisp and readable, yet beneath that clarity lies the subtle, living interplay of ink control—absorbing, releasing, and adjusting the brush tip. It is a personal signature that never overshadows the composition nor devolves into affectation.

The Aesthetic Value of Shen Xinde’s Small Xing-Kai (沈新德小行楷的书法美学价值)

The allure of small script lies primarily in its “refined intricacy” and “elegant charm.” In contrast to the sweeping grandeur of large characters, small xing-kai conveys the writer’s personality and cultivation with precision. Shen Xinde’s pieces show every stroke executed with discipline, each character rendered with care, yet they retain a certain nonchalant grace. The delicate interplay of lifting and pressing feels both meticulous and unhurried; the interplay of circular and angular shapes suggests a traditional Chinese view of “balancing opposites,” echoing the idea of “heaven is round, earth is square.” His works exude the upright, graceful poise of the literati and reveal the writer’s tranquil state of mind and close engagement with ancient principles.

Throughout Chinese calligraphy history, literati have often favored small characters for their capacity to reflect “self-cultivation” and “introspection.” Shen’s small xing-kai, precise yet gently understated, encapsulates scholarly temperament and aspiration. It also mirrors the contemporary calligrapher’s desire to rediscover classical sensibilities and a spiritual anchor in a world of relentless pace.

Above all, line quality is the soul of calligraphy. To judge a calligrapher’s caliber, we often start by assessing the vitality of their lines. In Shen’s small xing-kai, the energy stems from his deft combination of central-tip and side-tip techniques, along with carefully modulated lifting and pressing. Every turn is both rule-abiding and alive. Whether at the initial downward touch of the brush, mid-stroke adjustments, or the final closing, each line has a tension that is “tight but not stalled, relaxed but not loose.”

This refined linear language imbues the entire work with life, eschewing purely stiff neatness or freewheeling abandon. In his xing-kai, the flow of strokes across and between characters feels like a soft breeze or murmuring water, exemplifying the highest calligraphic ideal of “shaping with line, imbuing line with spirit.”

Shen’s small xing-kai also suggests a distinctly Eastern aesthetic. The texts he writes are often poetry, classical verses, or short Buddhist epigrams, and the interplay of ink and text merges the literary with the pictorial. The rhythmic brushstrokes resonate with the cadence of the words, letting viewers “read” the emotions in the ink as they read the text. When the writing evokes scenery, it hints at the vastness of mountains and rivers; when it touches on Zen wisdom, the intervals between characters flow with a sense of emptiness and clarity.

This threefold unity of text, brush, and meaning elevates Shen’s small xing-kai beyond mere technical demonstration. It becomes a comprehensive aesthetic experience—tranquil yet continually in motion, traditional yet resonating with the present—offering a beauty that bridges time.

Insights for the Contemporary Calligraphy World (对当代书法界的启示)

Modern calligraphers often grapple with the dual challenge of preserving tradition and seeking innovation. Shen Xinde’s works exemplify a viable path: in-depth study of classical masterpieces, supplemented by broad absorption of multiple stylistic streams—rather than rote imitation of a single master. Only by grasping the brushwork and spirit of Wang Xizhi, Zhao Mengfu, Mi Fu, Wen Zhengming, and others can an artist integrate and refine these influences to forge a distinctive synthesis.

At the same time, one must remain vigilant against the risk of haphazard mixing. The key to Shen’s success in merging diverse traditions into his own brush language is his unwavering commitment to strong composition and line quality. “Adopting widely” does not mean “disordered patchwork,” but rather a deliberate process of experimentation, editing, and polishing—so that each stroke and character maintains its individuality yet aligns with the unified mood of the piece.

Compared to large-scale xing-cao (行草) works, small xing-kai remains uniquely relevant in contemporary society. As public interest in traditional culture revives and many seek more “refined” ways of living, the demand for elegant small script—for letters, colophons, fan surfaces, frontispieces, and decorative art—is far from extinct. Shen’s small xing-kai demonstrates that this script can transcend mere regularity and can be explored through layout, brush dynamics, and ink variation, opening new horizons for modern art. If calligraphers integrate such skills into today’s social and cultural contexts—say, in public spaces or arts initiatives—they can promote traditional writing while injecting a richer humanistic ambiance into everyday life.

In sum, Shen Xinde’s small xing-kai, nourished by Zhao Mengfu and the Two Wangs, channels insights from Mi Fu and other masters of xing-cao, and then reinterprets them to create a style that is both warm and lively, yet firmly grounded. When viewed alongside classical small xing-kai, his works adhere strictly to form, composition, and brush intent, yet also embrace the subtle nuances of rhythm, arrangement, and ink control to broaden the expressive possibilities of the script in a contemporary context.

Such a practice of “melding tradition and the present” not only reveals Shen’s exceptional mastery and aesthetic perspective but also offers valuable inspiration for the calligraphy community, especially those pondering how to balance the classical with the modern. The refined lines and rich feeling that animate his small xing-kai highlight the form’s enduring allure and relevance. For any fellow enthusiast devoted to “holding true while innovating,” Shen’s explorations and achievements merit serious appreciation and study.

As the ancients often said, “The transformations of dragons and snakes under the brush ultimately arise from the mountains and valleys in one’s heart.” In our fast-paced era, calligraphy’s introspective, transcendent nature stands out all the more. Shen Xinde’s small xing-kai seamlessly unites a literati sensibility, time-honored brush technique, and a modern taste for balance, conveying a one-of-a-kind aesthetic through lines that are by turns taut and relaxed, still yet subtly in motion. Such a return to traditional roots, infused with contemporary resonance, is both a salute to the spirit of the old masters and a hint at fresh horizons in today’s calligraphy. Perhaps maintaining reverence and an exploratory mindset is the best stance any modern calligrapher can take.