A Survey of the Ten Major Calligraphy Masterpieces by the “Sage of Cursive Script,” Huai Su (怀素)

盘点“草圣”怀素十大书法作品

Source: Wenbo Tianxia (文博天下)

【Editor’s Note: Huai Su (怀素), a Tang Dynasty calligrapher celebrated as “the Frenzied Su,” cultivated an unparalleled cursive style characterized by lean, powerful strokes and spontaneous energy. Over time, he produced several influential works. The Self-Narration Scroll (《自叙帖》) is a wild cursive masterpiece detailing his life, praised for its continuous momentum. In contrast, the Small-Cursive “Thousand Character Classic” (《小草千字文》) stands out for its refined, measured approach, earning it the title “Thousand-Gold Scroll.” The Scroll to the Holy Mother (《圣母帖》) demonstrates Huai Su’s more contemplative, solemn style, while the Bamboo-Shoots Scroll (《苦笋帖》) epitomizes grace and spirited brushwork. Treatise on Calligraphy (《论书帖》) displays a tighter structure, revealing another facet of his talent. The Fish-Eating Scroll (《食鱼帖》) resonates with a lofty grace and expert brush control. His Large-Cursive “Thousand Character Classic” (《大草千字文》) exists in multiple versions, each prized for its archaic vigor. The Forty-Two Chapters Sutra (《四十二章经》) is a monumental project, reflecting his dedication to Buddhist texts. Finally, the Cangzhen Scroll (《藏真帖》) and the Lü Gong Scroll (《律公帖》), both revered as “Three Cangzhen Scrolls” works, blend influences from Wang Xizhi (王羲之) and others, showcasing Huai Su’s mastery. This canon cements Huai Su’s legacy as a giant in Chinese calligraphy. His legacy continues to inspire calligraphy aficionados.】

Huai Su (怀素), a renowned Tang Dynasty calligrapher and one of the greatest figures in the history of Chinese calligraphy, was tonsured as a monk from a young age. In his spare hours of meditation, he immersed himself in cursive script, gaining fame alongside Zhang Xu (张旭); together, they were dubbed “the Mad Zhang and the Frenzied Su.” This pairing of giants created a dual-peak landscape in Tang calligraphy and ushered in two monumental summits in the annals of Chinese cursive. Huai Su’s calligraphy is lean and forceful, brimming with swift, natural energy—like driving rain or a whirlwind, changing with every stroke. His art is unbridled yet steeped in discipline, endowed with endless variation. Viewing Huai Su’s cursive script always leaves one with a sense of exhilarating abandon.

Today, let us take stock of Huai Su’s ten major calligraphy works. Which one captivates you the most?

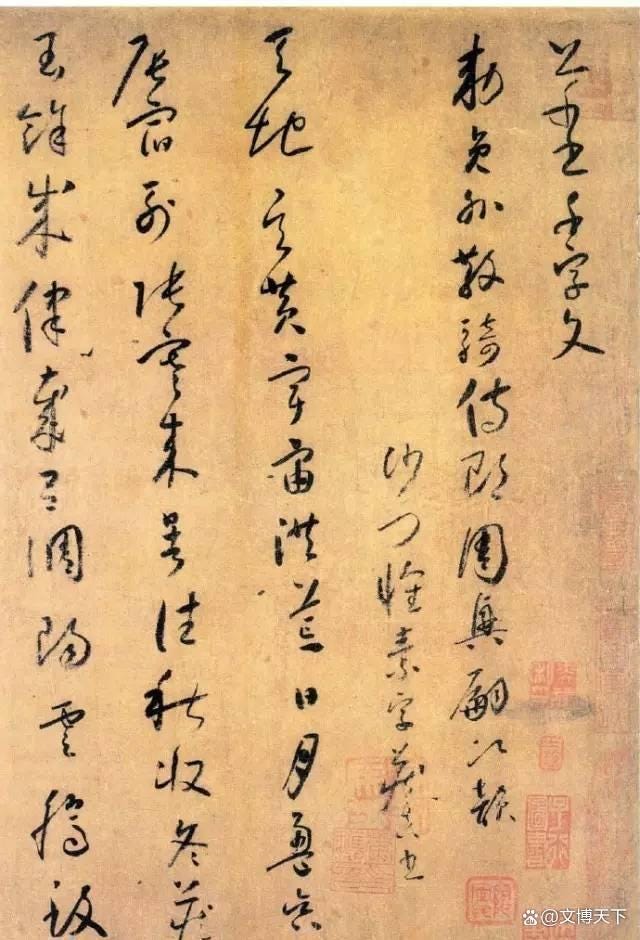

Self-Narration Scroll (《自叙帖》):

Created in 776 CE (some say 777 CE), on paper, measuring 28.3 cm in height and 775 cm in length, comprising 698 characters. The text offers a brief account of Huai Su’s life while recording verses dedicated to him by Yan Zhenqing (颜真卿), Zhang Wei (张谓), Dai Shulun (戴叔伦), and others. The entire piece is written in wild cursive, each stroke executed with a central tip, as though drawn with a stylus in sand, free and unrestrained. The scroll highlights a continuous cursive momentum, with the brush turning up and down, darting left and right, and rising and dipping in swift or slow, light or heavy gestures. Though bound by solid rules, it teems with creative flourishes and restless vitality. Later generations hailed it as “the number one cursive under heaven,” ranking it among China’s “ten most celebrated calligraphy masterpieces.” It is housed today in the National Palace Museum in Taipei.Small-Cursive “Thousand Character Classic” (《小草千字文》):

A late work on paper comprising 530 characters. Because of its rarity among Huai Su’s extant pieces and the saying that each character was “worth its weight in gold,” it is also known as the “Thousand-Gold Scroll.” The style is both ancient and subtle, vigorous yet unadorned, with an elastic texture. Almost every character stands independently, with slender, spirited strokes that feel ethereal. The entire piece exudes coherence, surging onward like a single grand wave, achieving the artistic realm of “in wildness, the world becomes weightless; in drunkenness, one attains true essence.” Unlike the Self-Narration Scroll (《自叙帖》), it offers a wholly distinct style, both in structure and line, radiating the beauty of an artist who has matured alongside his art. Later admirers dubbed it “the greatest small-cursive under heaven.”

Scroll to the Holy Mother (《圣母帖》):

Completed in 793 CE, measuring 70 cm high and 139 cm wide, in 55 lines and 409 characters. Considered a masterwork from Huai Su’s later years, it stands in contrast to the fierce emotional rush of Self-Narration Scroll (《自叙帖》), whose impassioned vigor spills forth like a rushing torrent. Here, the Holy Mother Scroll is founded on mindful composure, seemingly a single petal of incense, solemn and reverent. Integrating elements of Wang Xianzhi (王献之), Zhang Xu (张旭), and even traces of the Han Dynasty’s “clerical cursive,” it emerges as a milestone in Huai Su’s oeuvre. The Qing-era calligrapher Liang Yan (梁巘) deemed this Huai Su’s best piece, outranking the Self-Narration Scroll (《自叙帖》). It is currently preserved in the Second Chamber of the Forest of Stone Steles Museum in Xi’an.

Bamboo-Shoots Scroll (《苦笋帖》):

Ink on silk, measuring 25.1 cm in height and 12 cm in width, with 2 columns of 14 characters in total. The calligraphy is graceful, and the ink retains a fresh intensity that aligns it closely with the style of the Two Wangs (二王). It is a remarkable gem among Huai Su’s surviving works. In the Qing Dynasty, Wu Qizhen (吴其贞) praised it: “The calligraphy is elegant and vigorous, its composition comfortable and flowing, showcasing the master’s transcendent brilliance.” The brush moves swiftly, with an effortless flourish; there is a palpable lift-and-press contrast, though always held to a centering principle. Lines at their most delicate are agile yet firm; at their heaviest, they are thick but never clumsy.In terms of shape, there is greater variation in outline size and interior spacing. Overall, the top portion is looser, while the lower portion tightens, imparting a two-section visual rhythm that feels personal and distinctive. It now resides in the Shanghai Museum

.

Treatise on Calligraphy (《论书帖》):

Ink on paper, measuring 38.5 cm by 40 cm. Compared to the wild cursive style of the Self-Narration Scroll (《自叙帖》) and the Bamboo-Shoots Scroll (《苦笋帖》), this piece features lean, ethereal strokes, compact structuring, and orderly composition. Throughout, it abides by classical standards, avoiding outlandish shapes and adhering to a tradition that can be traced back to the Wei and Jin dynasties, exuding a gentle, serene charm. The brushstrokes feel measured, and the spacing of characters and strokes is carefully balanced; each stroke arises from the brush’s center, ascending and descending in a clear rhythm. The poet Han Wo (韩偓) called it “characters that leap like dragons.”

Fish-Eating Scroll (《食鱼帖》):

Ink on paper, 29 cm high and 51.5 cm wide, 8 lines, 56 characters. Its calligraphy possesses a lofty and rounded grace, spirited yet never unruly, with brilliant brushwork and deft transitions. The lift and press of the brush are expertly handled. Along with the Bamboo-Shoots Scroll (《苦笋帖》), the Self-Narration Scroll (《自叙帖》), and the Treatise on Calligraphy (《论书帖》), it is one of the four surviving works by Huai Su still extant today. The Fish-Eating Scroll (《食鱼帖》) and Bamboo-Shoots Scroll (《苦笋帖》) together represent the hallmark style of Huai Su’s cursive from his middle to late periodsLarge-Cursive “Thousand Character Classic” (《大草千字文》):

There are three known versions of this work: the Lütian’an version, the Qunyu Hall version, and the Xi’an version. The Qunyu Hall version was part of the Arthur Sackler Collection in the United States. The Xi’an version was carved at the Forest of Stone Steles in Xi’an in 1470 by the city’s prefect, Yu Zijun (余子俊). It bears colophons from the Qing Dynasty scholars Wu Rongguang (吴荣光), Wu Yun (吴云), Shen Yinmo (沈尹默), among others. Its rubbings were collected by Yu Jingzhan (于景瞻) in the Ming Dynasty and later passed down to Wen Zhengming (文徵明), Wen Peng (文彭), Xiang Zijing (项子京), and others; further seals from Zhang Zhao (张照), Wu Rongguang (吴荣光), Wu Yun (吴云), Pan Shicheng (潘仕成), Zhao Liewen (赵烈文), and so on attest to its provenance. Taking the Xi’an version as an example, the style is archaic and substantial, leaning horizontally with flowing, unrestrained strokes that exude a strong rhythm.

The Forty-Two Chapters Sutra (《四十二章经》):

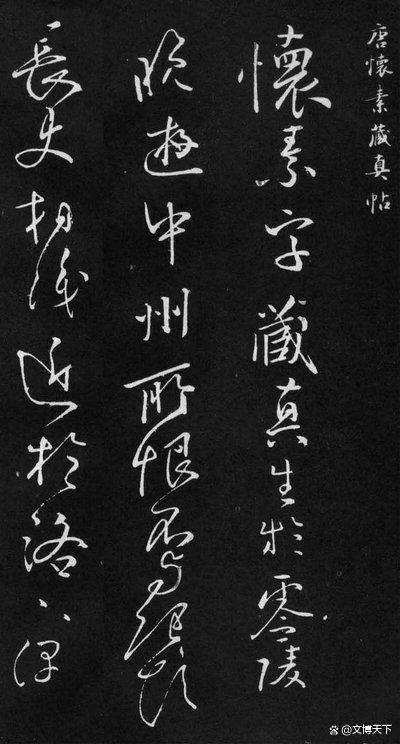

A rare, extensive work by Huai Su, some thirty feet long, in 248 columns totaling 2,663 characters, completed in the thirteenth year of the Dali era (circa Huai Su’s 42nd year). Inspired by passages about Mount Yandang (雁荡山) in this Buddhist text, Huai Su traveled to the mountain, where the head of a local temple asked for a sample of his calligraphy. Delighted to oblige, Huai Su copied this Theravada classic in the fine cursive for which he was celebrated. Afterward, it remained in temple archives, treasured as a sacred relic.The Cangzhen Scroll (《藏真帖》):

Known as one of the “Three Cangzhen Scrolls,” this is a masterpiece of Huai Su’s semi-cursive. The ink rubbings on paper span 6 lines and 51 characters, describing a journey north to seek instruction from preeminent figures, with particular emphasis on his time learning calligraphy from Yan Zhenqing (颜真卿). The brushwork is slender and powerful, while the character forms are rounded. The three characters “Yan Shangshu (颜尚书)” stand out magnificently, towering above the rest. In its final three lines, the writing grows swift and exultant, capturing Huai Su’s sense of enlightenment—an amalgamation of Zhong You (钟繇), Zhang Xu (张旭), and the lingering influence of Wang Xizhi (王羲之) and Wang Xianzhi (王献之), a treasure in the annals of calligraphy.

The Lü Gong Scroll (《律公帖》):

Another of the “Three Cangzhen Scrolls” and a quintessential work of Huai Su’s cursive, measuring 140 cm by 49 cm. Its spirit is reminiscent of the Two Wangs’ semi-cursive—smooth and fluid, brimming with fervor and panache. Its characters are elegant in structure, both wondrous and extraordinary, evoking the energy of dragons and tigers. The composition’s interplay of space has the gleam of jade and the brilliance of celestial bodies, an astounding visual display. It is inscribed together with The Cangzhen Scroll (《藏真帖》) and stands in the Third Chamber of the Forest of Stone Steles Museum in Xi’an.

Translated by the China Thought Express editorial team, seeking to connect ideas between Chinese and English-speaking readers.